Some time ago, my “cupcake” Google alert captured this provocative story: “More Philly bragging rights: We basically invented the cupcake.” Well, fancy that.

A field trip was in order. I put it on my to do list … and there it stayed. So close, yet I wasn’t dedicating the time to go there.

Then I learned that veteran pastry chef Nick Malgieri was doing a demonstration there in conjunction with the 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth. Count me in.

My mission was to investigate the Philadelphia cupcake legacy by day and attend the Malgieri event at night.

The Library of Congress food historian sent me a wealth of background information about the 19th-century cupcake author in question, Eliza Leslie.

I was aware that Leslie published the first documented “cup cake” recipe in her 1828 Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats. I didn’t know she was a Philadelphian, nor did I have an appreciation of her literary/culinary impact.

One source calls Leslie the “most influential cookbook writer of the 19th century.”

If it wasn’t for Eliza Leslie, American recipes might look very different. Leslie wrote the most popular cookbook of the 19th century, published a recipe widely credited as being the first for chocolate cake in the United States, and authored fiction for both adults and children. Her nine cookbooks—as well as her domestic management and etiquette guides—made a significant mark in American history and society, despite the fact that she never ran a kitchen of her own.

— Food historian Liz Susman Karp

With essential guidance from the Library of Congress researcher, I set out to visit some addresses where Leslie lived and attended culinary school.

According to contemporary author Becky Libourel Diamond, the first U.S. cooking school opened in Philadelphia and it was a student named Eliza Leslie who would later publish the founder’s recipes. Elizabeth Goodfellow didn’t record or publish the recipes she used at her eponymous Mrs. Goodfellow’s Cooking School.

When Leslie’s father died, her mother opened boardinghouses to support the family and Leslie presumably lived there. One address is 188 Spruce Street. Visiting the vicinity, I discovered that house number 188 doesn’t exist. One source referred to the address as Spruce a block north of Dock, but Spruce and Dock don’t presently intersect.

Another address of Mrs. Goodfellow’s Cooking School was 91/71 6th St. between Spruce and Pine Streets, according to food historian Patricia Bixler Reber. Walking 6th between Spruce and Pine, I saw charming old brick rowhouses with numbers in the 300s and 400s.

Following the map pinpoint to 91/71 6th, I find a brick bank across from Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. Another Leslie family boardinghouse was at 48 S 6th, which the map puts in the bank’s parking lot.

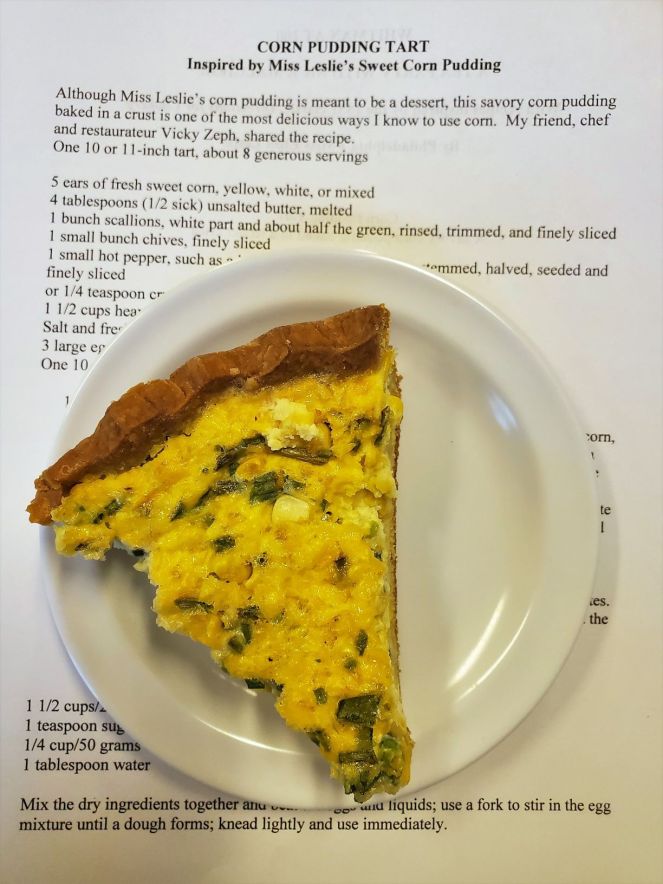

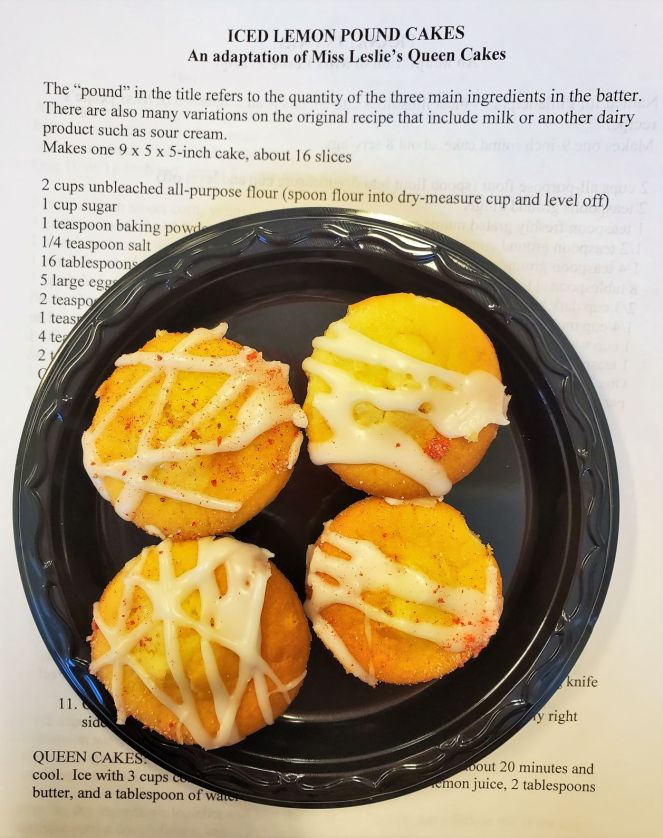

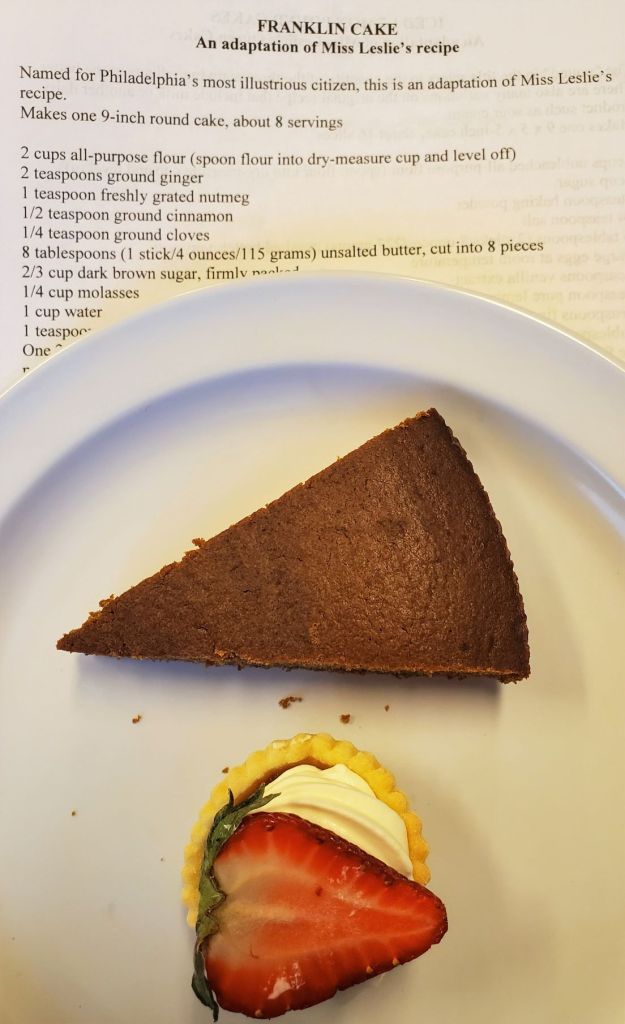

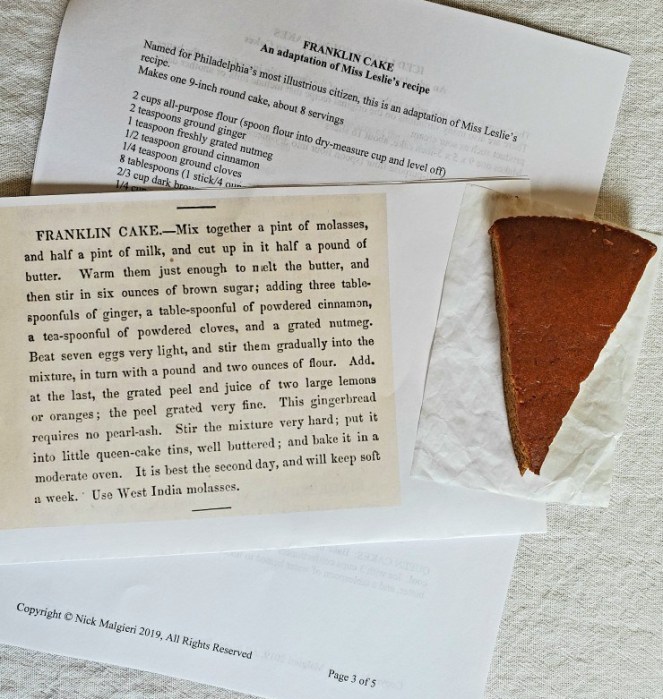

On to the Malgieri event, which became the linchpin that tied everything together. As it turned out, Malgieri baked cakes adapted from Leslie’s recipes. I didn’t know this was coming. Neither the event page nor the ticket site indicated that the cakes would be Leslie’s.

Leslie’s gingerbread cake is named after Ben Franklin. Here I picture it with Malgieri’s version of Leslie’s rhubarb tart. In the headnote, Malgieri writes, “these little tarts or others filled with seasonal fruit were a mainstay of the 19th-century tea table.”

Tired and foggy from the rigorous day, I smiled inside. The whole trip was something of a wild goose chase. I didn’t exactly know what I was looking for. Malgieri’s focus on Leslie validated my intuition. I was there to intake cupcake history centered around Leslie.

Here’s what’s prophetic: at every destination, there was a bookstore or writerly enterprise. I’d arrive at a location, get my bearings, attempt to find the precise address, view the panorama, and inevitably I’d see books.

Near the 134 S 2nd cooking school address, I found a shuttered historic building with stained glass called the Old Original Bookbinder’s. Before I researched it, I assumed it was an historic bookshop. How apropos. Upon investigation, I learned it has no connection to books, but is named after the proprietor of an old-time seafood restaurant. Fine, I can relate.

When it was time for my lunch break, I noticed 68-year-old Joseph Fox Bookshop across the street.

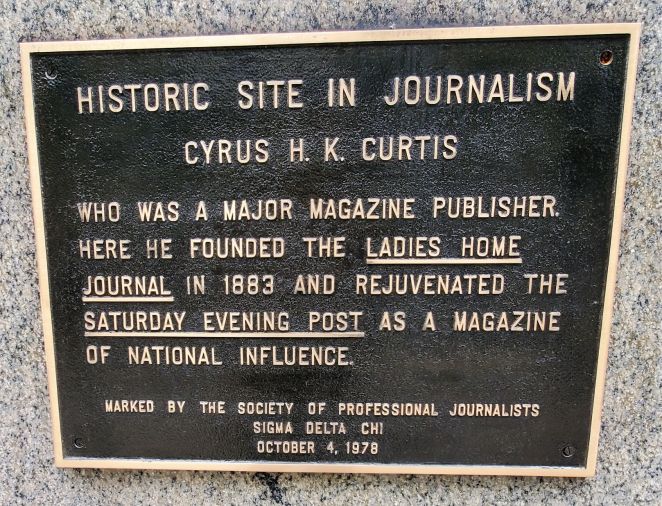

To borrow from youthspeak, I had all the feels at the 91/71 6th cooking school site. Personally and topically, my book project represents liberty, independence, and American history, so I appreciated the proximity to Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. Then I came to plaques informing me I was at the Curtis building.

The brick-and-mortar structures were concrete reinforcement of my mission. I was pro-actively looking for cupcake history and serendipitously met with the company of books. Books and cake history materialized before my eyes. It’s a good sign.